Storing times, and precision of float64

Posted on Fri 26 September 2025 in Software, last modified Wed 31 December 2025

This is the second article about how working with temporal information in computer systems. The first article was about contained some definitions about astronomical time and timezones.

This article describes options for storing temporal values in your programs, and their limitations. In particular, it describes two pitfalls that can happen when working with floating-point representations for times.

Numeric data types

Computers have a number of ways to represent numerical values, each with

their uses. Two most important formats for us are int64 and float64.

Both use 64 bits (8 bytes) to store values. They are the most commonly

used in modern systems for general-purpose computations in which memory

is not at a premium, and are widely supported across major programming

languages.

Further notes on Wikipedia.

Integers

int64 uses a binary (base 2) representation to encode an integer value

between -2**63 and 2**63 - 1 = 9,223,372,036,854,775,807 inclusive: that is, approximately 10**19.1 Positive

numbers (and zero) are stored in the obvious way, and negative numbers

are usually encoded using two's

complement.

Floating-point values

Fractional values are most commonly stored using a floating-point representation. Numbers2 are represented in the "scientific" or "standard" form

x = s * (1 + m) * 2**e

where:

- the sign bit

s in {-1, 1}specifies the sign of the number; - the mantissa

0 <= m < 1specifies the fractional part of the significand in base 2; and - the exponent

e in range(-1022, 1024)is an integer that determines the scale of the number.

The mantissa is stored using 52 bits, the exponent with 11, so alongside the sign bit, that makes 64 bits in total. Details on Wikipedia.

The term 1 + m is called the significand, containing the significant

figures of the number: this is a number in the interval 1 <= 1 + m < 2. "Floating point" refers to the fact that the decimal (binary?) point

may be moved to different locations by modifying the exponent.

This representation confers certain performance advantages: for example, to multiply two floats one simply multiples the two mantissae and adds the two exponents. Details about floating-point arithmetic on Wikipedia.

Precision limitations on floats

Details can be found on Wikipedia, but for us, the most important observations are the following:

- The exponent term

2**eallows both very large and very small numbers to be represented. - The mantissa is stored using 52 bits, which means that the maximum

precision of a floating-point number is 53 significant figures (in

base 2) – the extra significant figure coming from the

1 +term. - 53 bits of significance corresponds to about 16 digits; so the maximum

precision in decimals is about 16 digits. (Actually between 15 and 17

digits depending on the exact values of

mande.) - This relative precision is independent of

e. However, the absolute precision does depend one– the larger the number, the worse the absolute precision.

Unix time

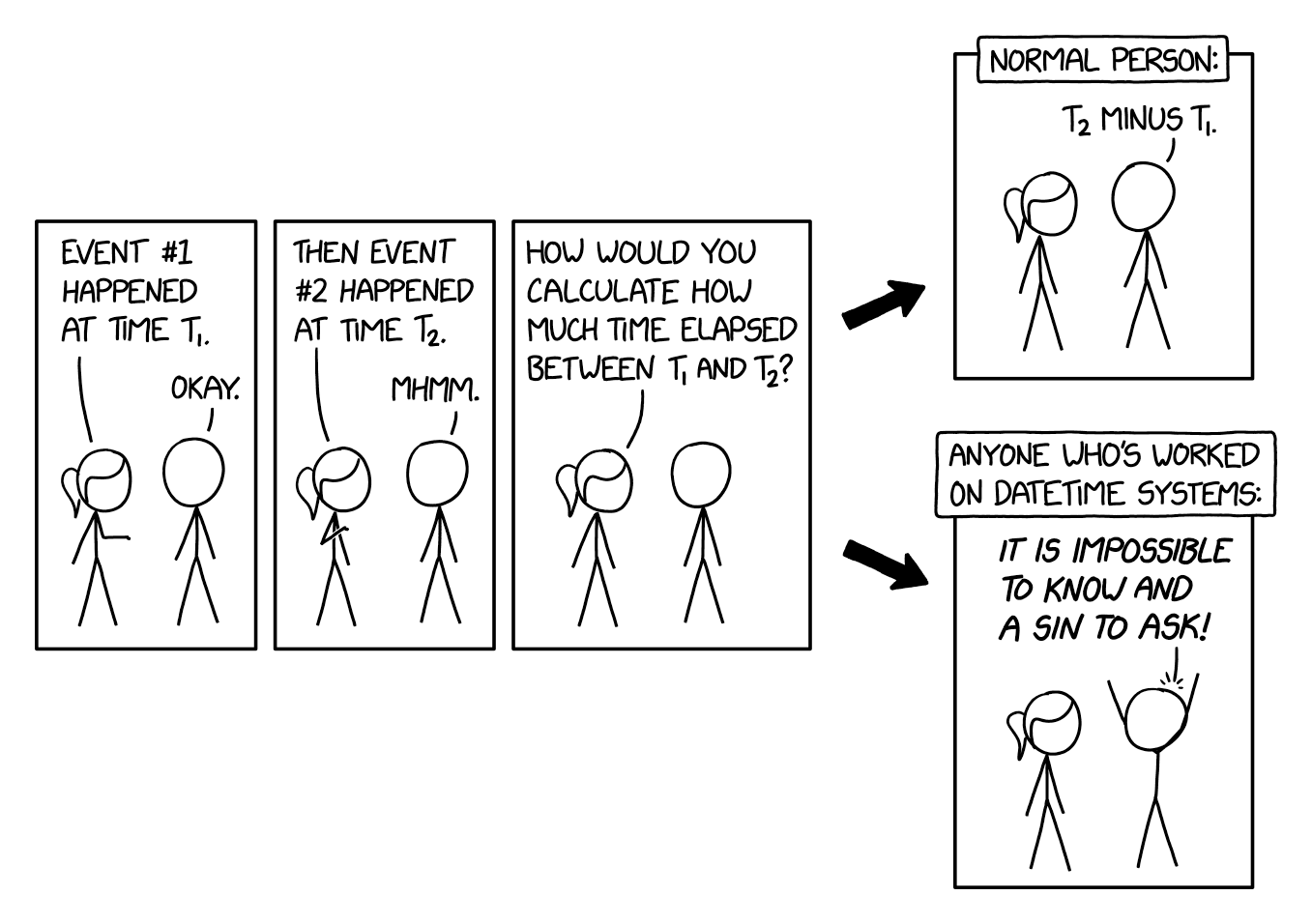

As mentioned in the previous post, there are actually two distinct concepts of time: relative time or timedelta, which refers to the interval between two events, and absolute time, which refers to the elapsed time since some globally-agreed upon epoch.

Most computers today use the Unix Epoch or simply Epoch (capitalised), which is defined to be 00:00:00 UTC (midnight) on 1 January 1970. The Unix time is then the number of seconds3 elapsed since the Epoch.

Unix time is very useful because it gives all computers a standard reference scale4. Computers can synchronise their clocks with each other using such means as NTP or LTC.

Limits on precision and workarounds

However, the fact that float64 values are limited to 15–17 significant

figures of precision can cause a difficulty when using Unix time in

applications that require high (sub-millisecond) precision.

As of 2025, the current Unix time is about 109 seconds; at worst, this leaves only 6 significant figures for fractions of a second, and the microsecond place is subject to rounding errors.

One microsecond may seem like an insignificant amount of time for general computation, but it does have practical consequences, especially when considering performance: many common computations execute on the order of a few hundred nanoseconds and so a microsecond of imprecision is unacceptable.

For a more tangible example, consider audio that is sampled at 48 kHz: the interval between two samples is only 21 microseconds. Although this is an order of magnitude larger than the rounding error, the imprecision in the Unix time may worsen as further computations – especially subtractions – are made.

Thus it is advisable to avoid using Unix time in seconds stored as

float64s when precision is required. There are a few alternatives

available.

Use timedeltas

While Unix time is useful for unambiguously storing an absolute time, in applications that require so precise measurements the absolute time is usually not of interest. Thus, depending on the application, it may be more appropriate to work with relative times.

Most modern computers offer two clocks. One is persistent, continuing to count when the system is powered down: this allows the computer to give an absolute time (usually Unix time); the clock is periodically synchronised using NTP or some other protocol. The second clock, sometimes called the performance counter, starts counting from zero when the computer starts up, but has much better precision (usually nanosecond-level): this makes it appropriate for measuring small timedeltas, such as the time taken for a computation to finish (hence "performance").

In Python, the time according to the performance counter can be obtained

using the functions time.perf_counter() and time.perf_counter_ns().

The problem with the performance counter is that it is only good for timedeltas and is tied to the particular instance; it is of limited value when synchronising across machines since it is not appropriate to compare the performance counter readings from two different machines.

Use a different epoch

Another option is to use a later epoch, say, the year 2000, instead of the Unix Epoch of 1970. The 30 year difference works out to $946,684,800$ seconds. The big disadvantage of this is that all epochs are arbitrary, but some are less arbitrary than others: for better or for worse, 1970 is the default in almost all systems and it would be a chore (and an inevitable source of bugs) to ensure that all parts of your code, across all your systems, are using the same epoch.

The time of day (seconds elapsed since midnight) may be a good option: storing the date and the time separately. The time of day is at most 86,400 seconds5 and the date may be stored as an integer number of days since the Epoch: there is plenty of precision.

But this comes with its own challenges. Different timezones will cause two simultaneous events to be recorded as different times, and possibly being on different days. An activity that runs overnight will start and finish on different days, and the start time-of-day will be greater than the end time-of-day. This introduces further complications.

Use integers

If it is required to use a precise absolute time, then a good option is

to store the Unix time not as seconds in a float64, but as nanoseconds

as an int64. As mentioned above, this allows values as large as

2**63-1, or about 1019, to be stored

exactly. The current Unix time in nanoseconds is about 1018

so this remains a viable option... at least until the year

2262.

Alternatively you can use microseconds, or 100-nanoseconds, or whatever

precision you require; again, it is a chore to ensure that all parts of

the system use the same units and conventions.

A possible disadvantage of this approach is that many numerical functions take and return floating-point values and so a lossy conversion to a float must be made at some point. This is not a problem in practice, since these functions cannot be physically meaningfully run on raw time values anyway: an expression such as $\sin(3,\mathrm{seconds})$ is not dimensionally consistent; and if you do find yourself needing to compute such an expression, something has already gone wrong and precision should be the least of your worries.

Conclusion

- This previously read

2**32; thanks to Pavel Roskin for the correction. ↩ - Specifically, the so-called normal

numbers. There are also a number of special values such as subnormal

numbers, zeros,

infandnan, which I won't talk here; althoughnanplays an important role in representing missing or unknown values. ↩ - Ignoring leap seconds. ↩

- All this discussion ignores relativistic effects. ↩

- Again, ignoring leap seconds. ↩